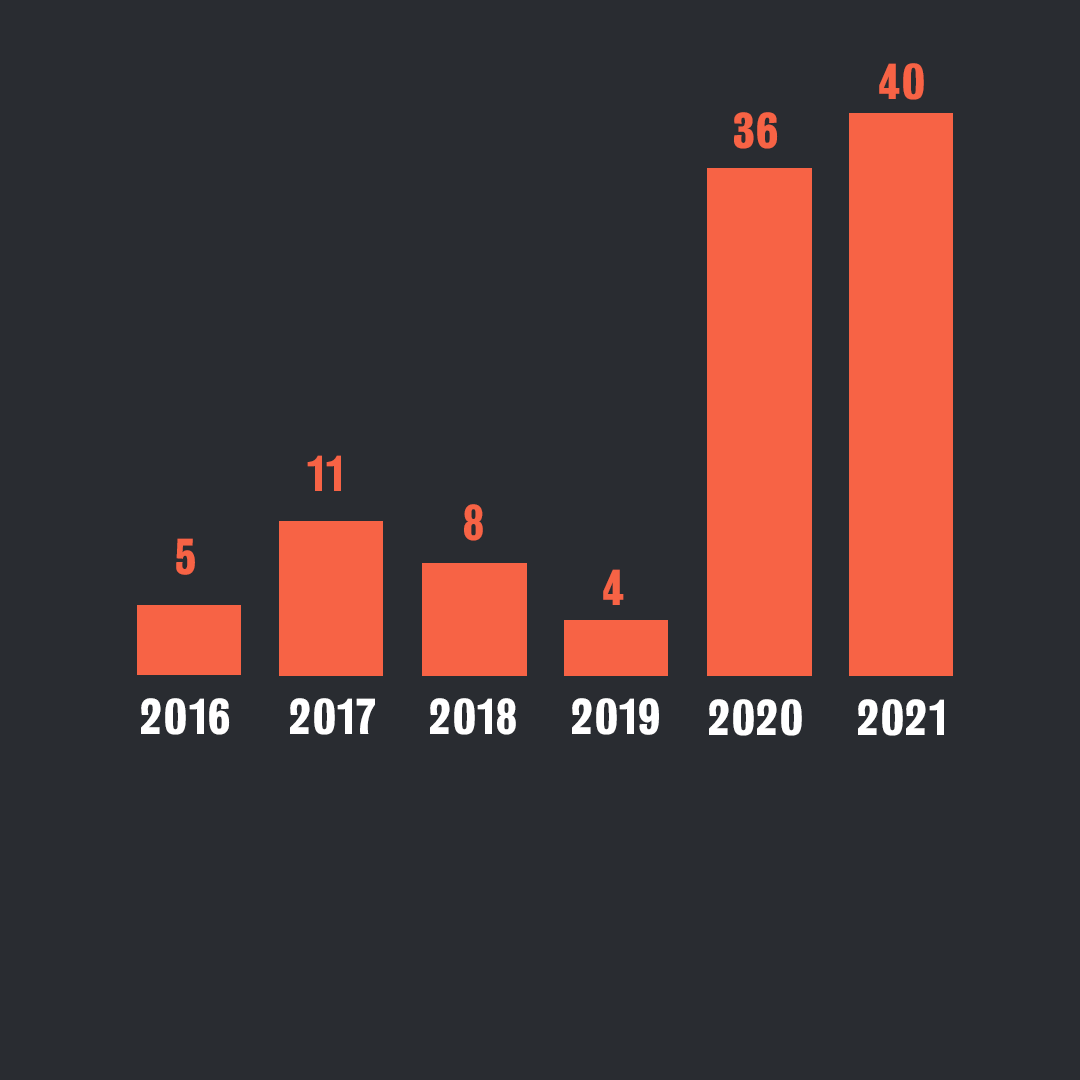

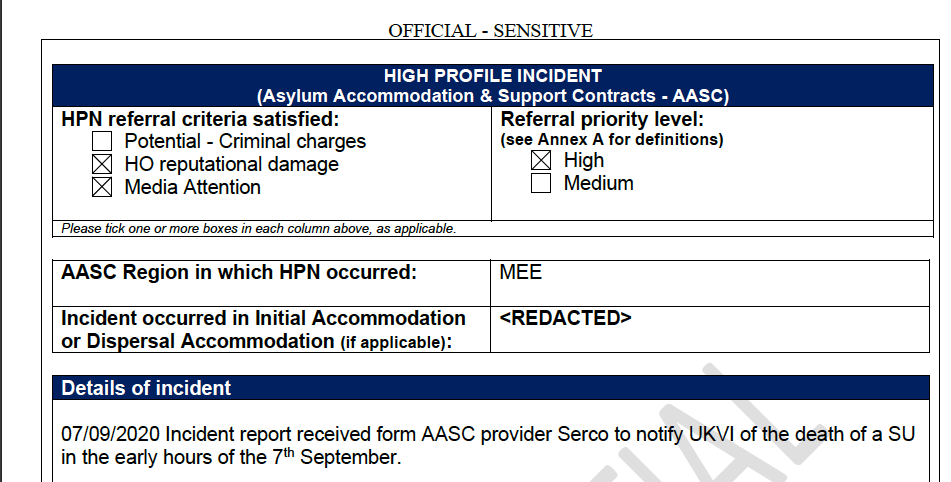

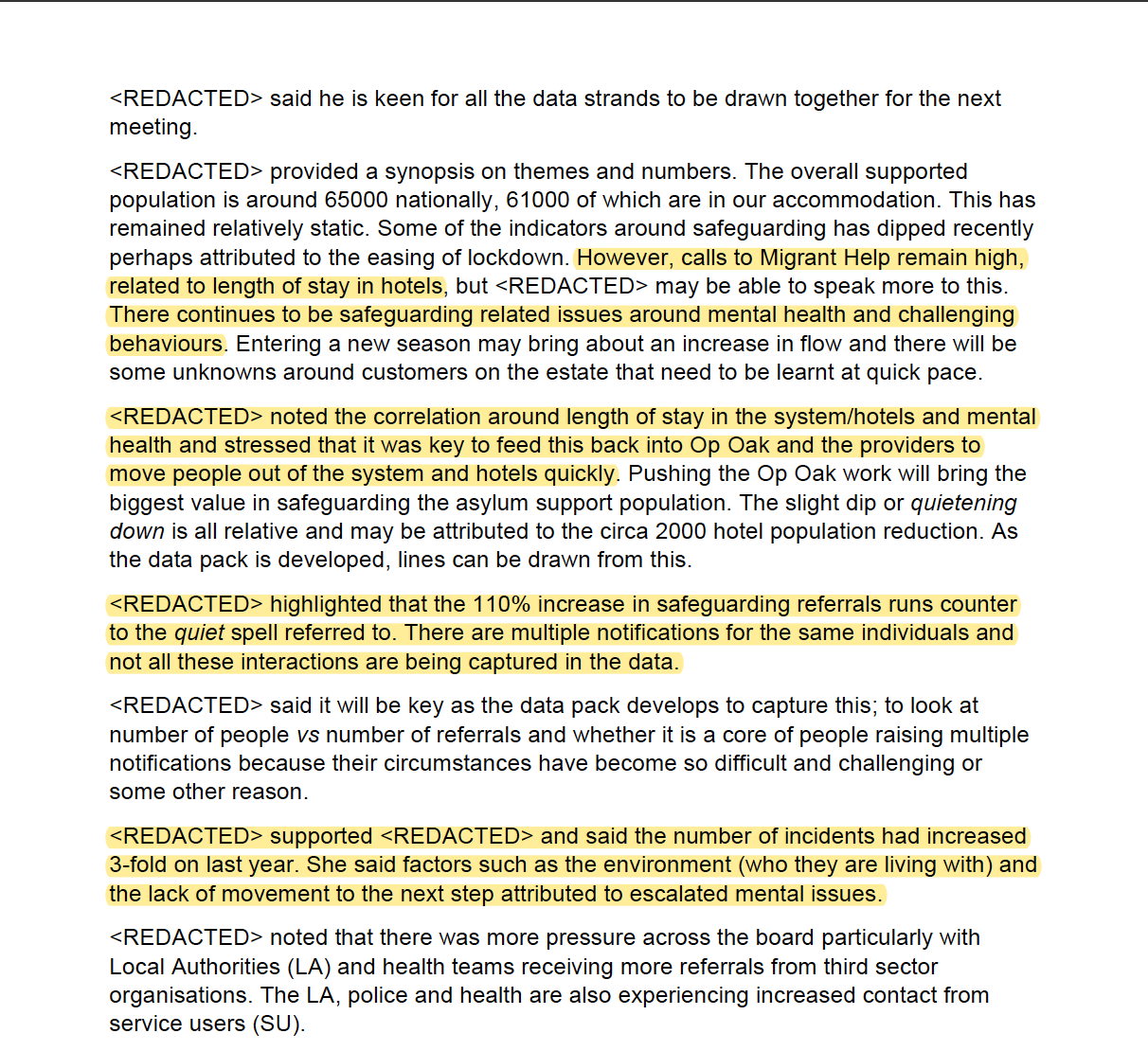

Dozens of at-risk asylum seekers died during pandemic amid alleged safeguarding failings

Published on 25 June 2022

107 asylum seekers provided Home Office housing died between April 2016 and May 2022

Reports Jessica Purkiss, Aaron Walawalkar and Mirren Gidda, Liberty Investigates journalists; and Eleanor Rose, Liberty Investigates editor