Deportation fears after police collect asylum seeking children’s biometric data

Published on 16 April 2023

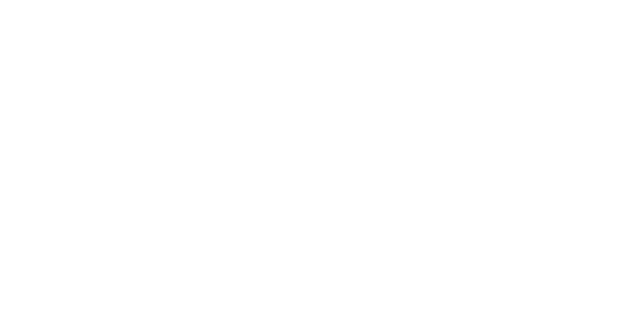

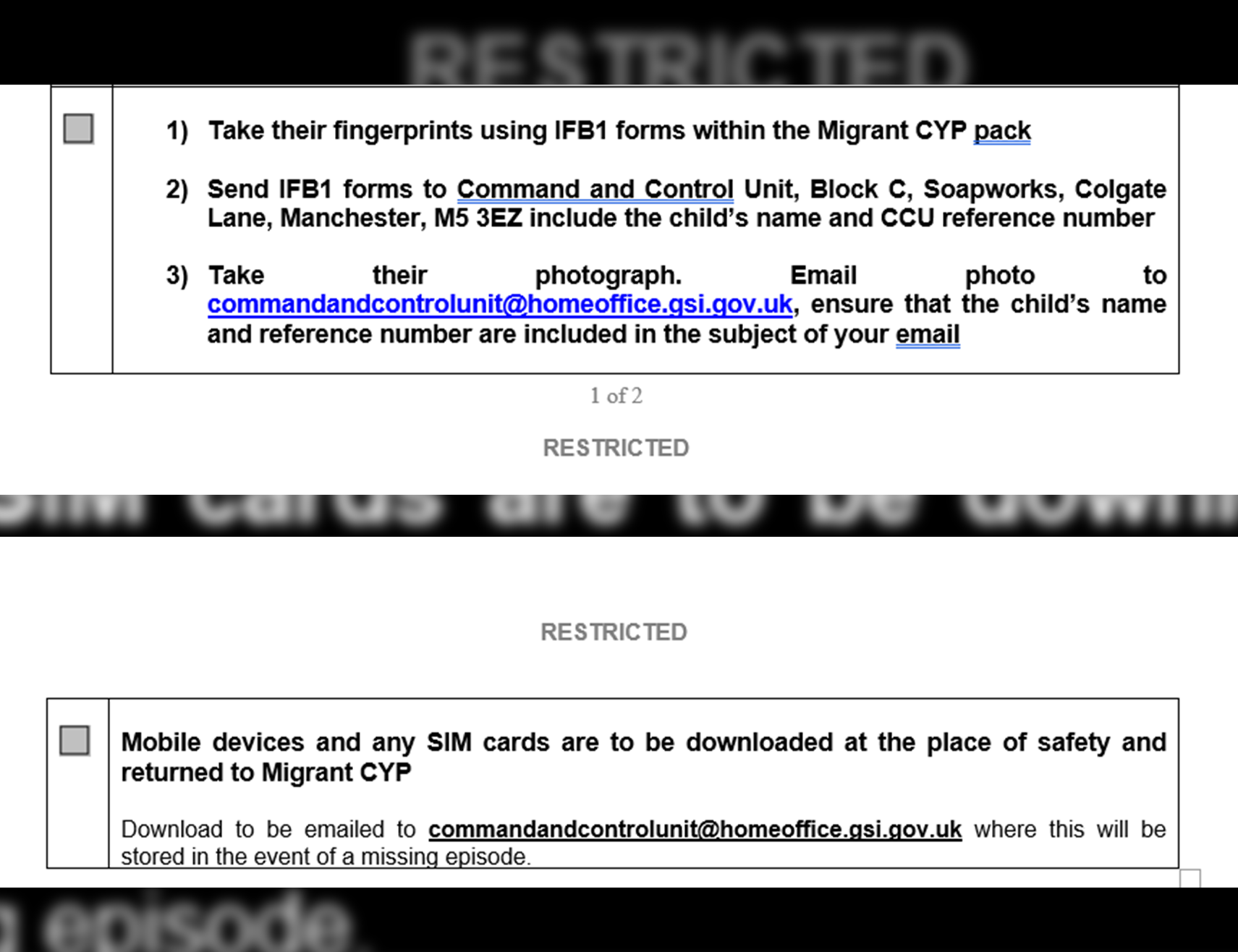

Police collect children's biometric data, which is then shared with the Home Office

Reports Mirren Gidda, for Liberty Investigates. Edited by Eleanor Rose, Liberty Investigates editor and Steve Bloomfield, Head of News at the Observer.