Fears UK coastguards left children adrift on small boats before Channel tragedy

Published on 04 March 2024

A family is helped to shore as a group of people thought to be migrants are brought in to Dungeness, Kent, by the RNLI following a small boat incident on 20 November 2021. Credit: PA / Gareth Fuller

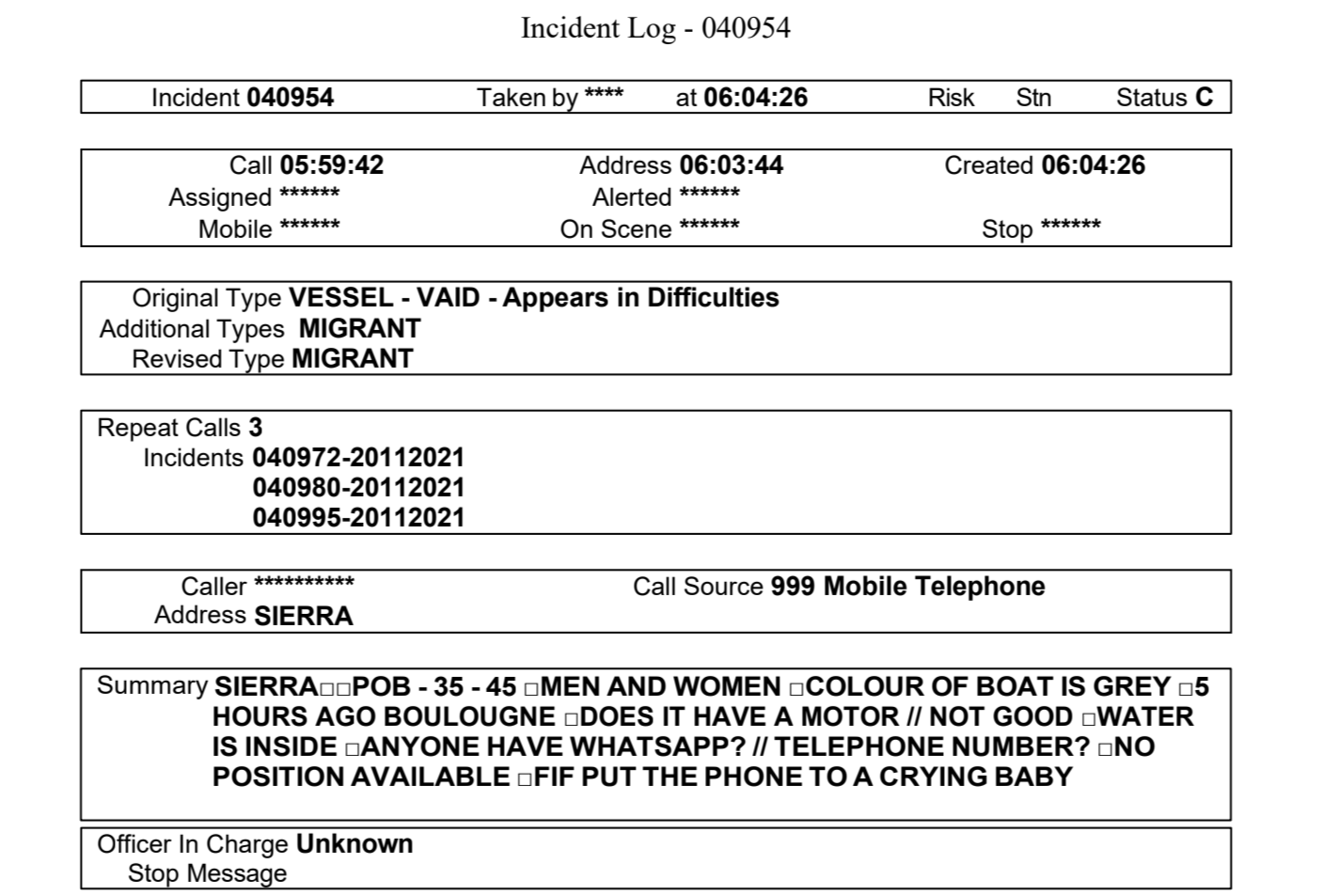

New evidence lays bare how under-resourced rescuers were 'overwhelmed' and sparks calls for an investigation into fate of children reported at sea

Reports Aaron Walawalkar and Harriet Clugston for Liberty Investigates, and Mark Townsend for the Guardian.