Government ignored its own pre-pandemic prison advice

Published on 20 April 2020

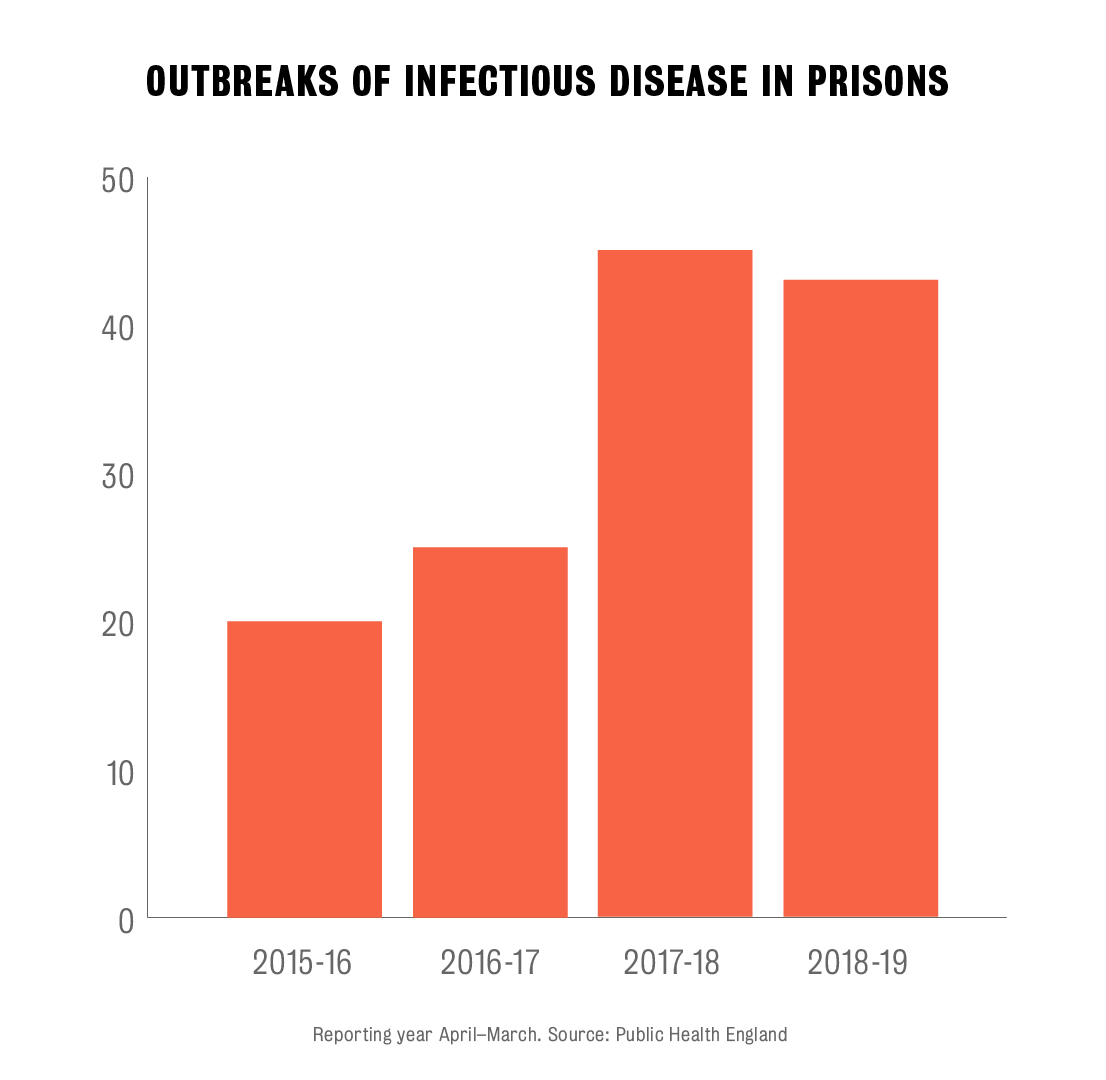

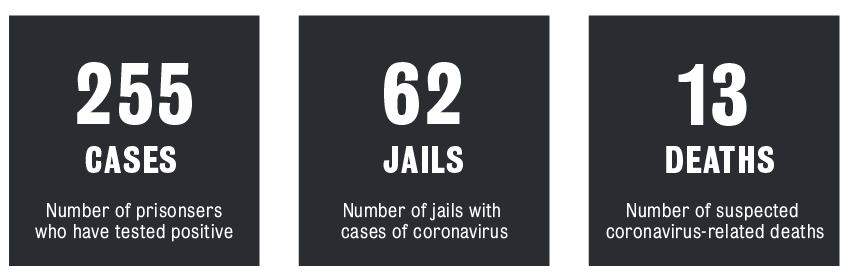

new data analysis demonstrates that UK prisons were fighting a rising tide of infectious outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reports Eleanor Rose, Liberty Investigates journalist.