‘Horror beyond words’: Inside the UK coastguard in the weeks before the Channel disaster

Published on 29 April 2023

Image: Alamy

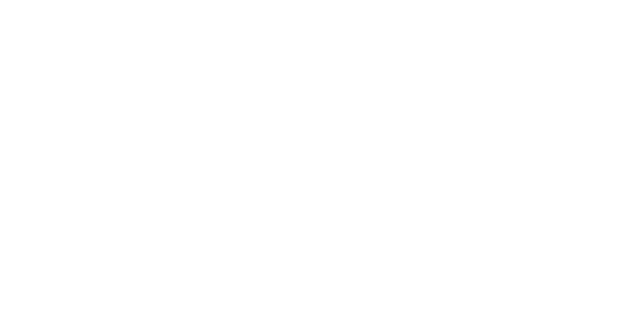

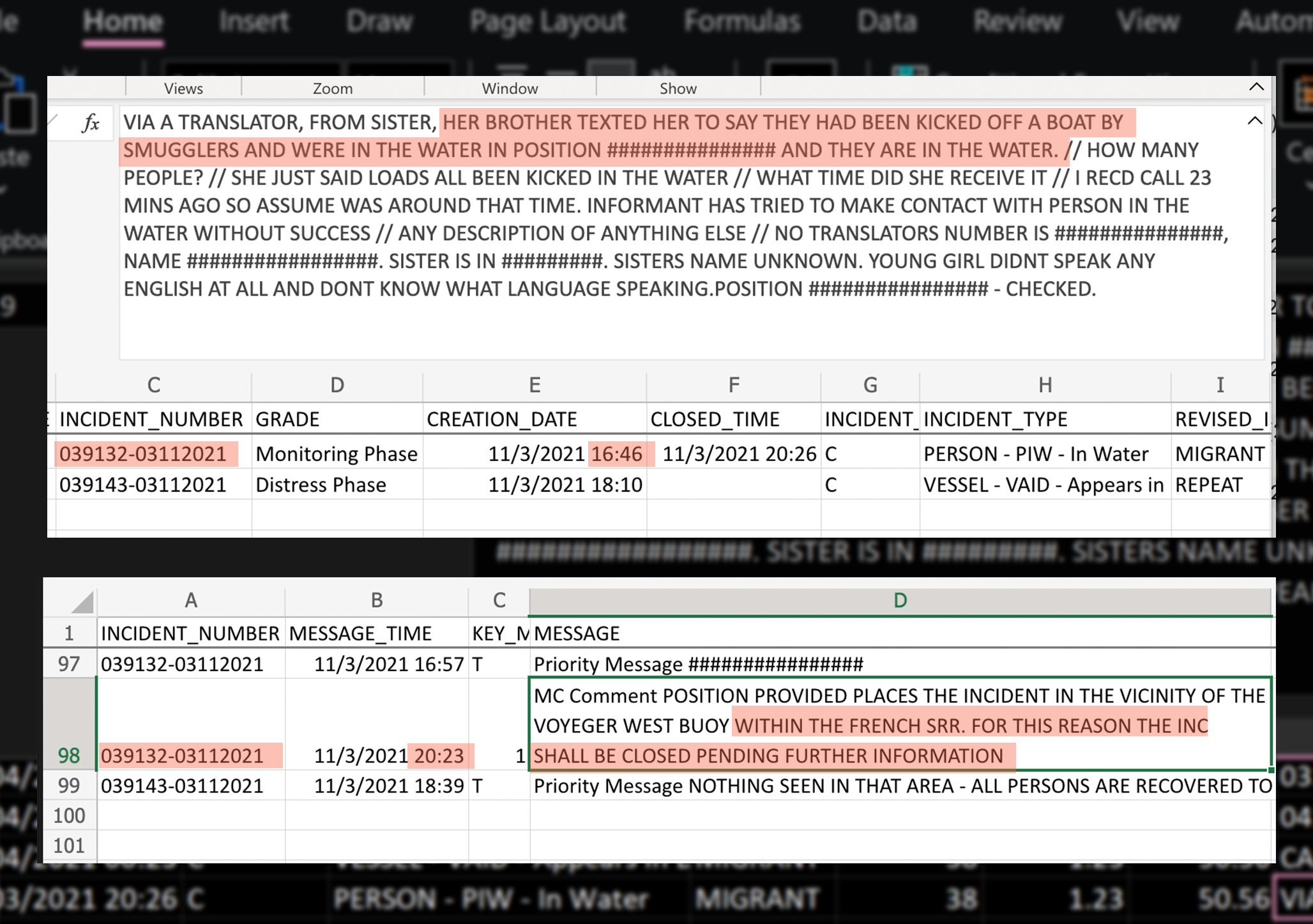

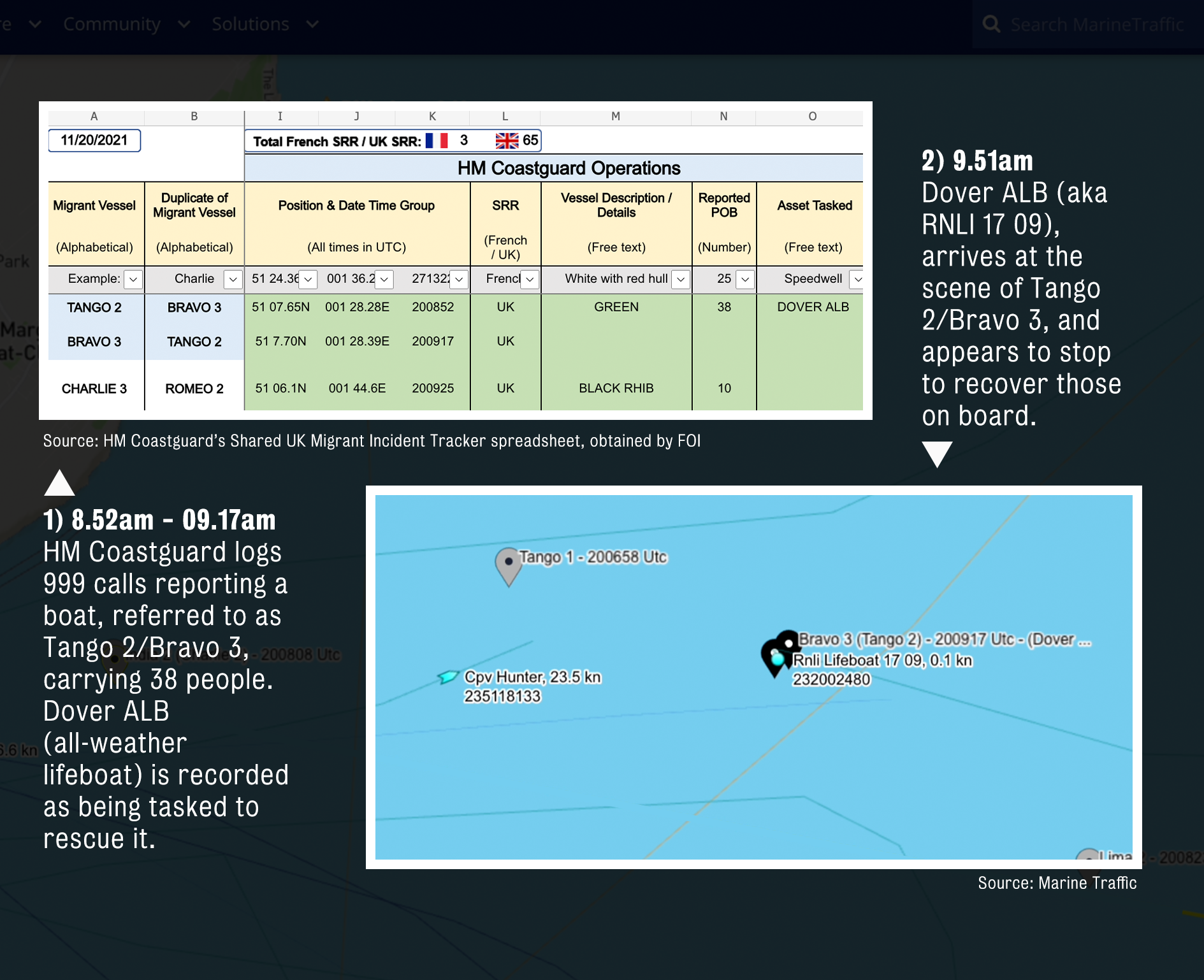

Investigation reveals that understaffed Dover control room was overwhelmed by calls before 27 died at sea

Reports Aaron Walawalkar, Liberty Investigates journalist; Eleanor Rose, Liberty Investigates Editor; and Mark Townsend, Home Affairs Editor at the Observer.