Coronavirus / Detention

“I can’t sleep”: COVID-19 fears inside immigration detention centres

Posted by Eleanor Rose on 17 Apr 2020

Before the pandemic, immigration removal centres (IRCs) held between 1800-3500 people at any one time. There are seven such centres across the UK. Migrants are locked in cramped facilities in conditions described as prison-like, though some have never been convicted of a crime, and the rest have already served their sentences. Many are survivors of trafficking and torture, or have lived in the UK since they were children. About 50 percent have claimed asylum at some point.

By law, the Home Office can only detain a person when there is a realistic prospect of deporting them imminently. But travel is now heavily restricted around the globe. A legal challenge brought to the High Court on 26 March by the group Detention Action, which supports those held in the centres, called on the Home Office to release detainees with health problems and all those from 50 countries to which deportation is currently impossible. The judge dismissed it on the basis that the Home Office is already taking action to protect vulnerable detainees.

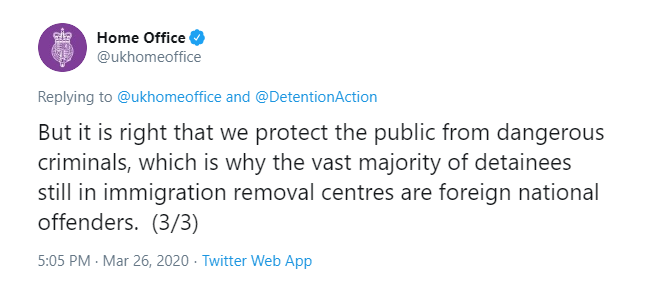

Although the Home Office has now released hundreds of detainees, it is thought that several hundred were still being held across several IRCs. In a response to Liberty Investigates, the Home Office did not give a figure, but said it is following guidance from Public Health England, with “robust measures” in place to deal with coronavirus cases supported by the High Court decision. In a recent tweet, it also said the “vast majority” of those still in immigration detention were “dangerous foreign criminals”.

We spoke to three of them. None had been convicted of offences that could be deemed violent or sexual in nature.

“I can’t sleep”: Anne, Yarl’s Wood

“Anne”, who asked us not to publish her real name, has lived in the UK since she was a child and is now in her 30s. Her young son is a British citizen.

Anne was expecting to be released at the end of her sentence for a non-violent crime two weeks ago, but instead was moved straight from prison to Yarl’s Wood IRC. This is common when the Home Office wants to deport a foreign national offender, but comes as a shock to many – especially in this case, in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis.

When I finished my sentence, I thought I was going to go back to my baby – and then they sent me here all of a sudden. I was really distressed, really depressed, and every time I ring my son he’s like, “How come mummy’s still not home?” He watches the BBC and he says, “Mummy, I’m watching about Corona. Mummy I want you to be here with me, I’m scared.”

"We came from different backgrounds with different stories, but everyone’s scared"

We just want to get out. We’re going to have to fight our cases [on the] outside, but why keep us here in this pandemic if it’s safer at home? [Custody officers] come in and out of here, and we don’t know if they’ve got the virus. They say [we should] self-isolate, but you tell me how to keep distance between these people when everyone’s suffering and you can’t be on your own in your room because you’re so depressed? I can’t sleep on my own.

We came from different backgrounds with different stories, but everyone’s scared. [The Home Office] were saying that most of us are criminals. Yes, okay, we might be “bad people”, but we’ve done our time, we’ve had our punishment already. It’s just because we don’t have a British passport, that’s why. Most of us have learned our lesson, we just want to be home with our family.

I’ve been in the UK most of my life, I have a British child. I tried so hard in prison to take all the rehabilitation courses they offer, to try to improve myself. They take you on the courses and keep promising you’re going to get a job when you get out, but before you could get a job, they deport you. You’ve done everything you could in prison and they never open the door again for you.

When I arrived, there were 35 people here [in Yarl’s Wood]. Now it’s 18 or 19. It’s so hard because you see people come and go, and you don’t know when it’s your turn. I don’t think I’m going tomorrow, I really don’t have the feeling I am.

“They’re not wearing masks”: Yuki Kung, 25, Yarl’s Wood

Yuki arrived in the UK two years ago. She suffers from asthma, an underlying health condition that is said to put those with it at a higher risk of becoming seriously ill if she contracts COVID-19.

I wear a mask outside my room, and when I get back in my room I wash my hands. People with health conditions are being put on a support plan where they’re supposed to deliver our meals to our rooms, but they’re not. We have to go to the dining room to get our meal. The corridor is narrow, only one and a half metres, so people pass close to you. The other day my friend ordered a side salad and it had mould on it.

Yesterday, I went to get dinner and forgot to wear my mask. The officer told me: “You can’t get your dinner without your mask on.” I just walked away, because I felt ridiculous. I know the masks are helping us, but the officers are the ones who keep going in and out every day – and they’re not wearing masks.

I’m feeling OK right now, but people in here are depressed. Some can’t sleep at night. We’re trying very hard to do social distancing but, you know, we are from jail – we’ve seen many things. Sometimes, if you’re not there, your friend commits suicide.

Serco, the private firm that runs Yarl’s Wood, responded: “All government guidelines on keeping our staff and the residents safe are being carefully followed, including allowing residents to have their meals in their rooms, and there is plenty of PPE for the staff. The food continues to be of a high standard.”

People in here are depressed. Some can’t sleep at night.

I wear a mask outside my room, and when I get back in my room I wash my hands.

“You can lose your mind”: Sharmake Mohammed, 21, Colnbrook

Sharmake was born in Holland and moved to the UK aged six. His younger siblings are British citizens. He says that as a teen, he was groomed by a gang. He has served 11 months for an offence related to Class B drugs. He was taken from prison to Colnbrook IRC in December, where he has been held since.

They’re still opening our doors and the regime is running as usual – but a lot of things have been closed, such as the shop, the barber shop, and welfare – you have to book an appointment now. Now I’m on a wing with just 13 or 14 people, isolated from the other wing.

Anything I know about coronavirus is all from the news. Me personally, nobody’s communicated to me what to do or what not to do – I’m just learning off common sense. They’re not letting me know what’s going on with my case, they’re not letting me know if I’m liable for release. I know [Holland] isn’t taking any flights at the moment, so I don’t understand why I’m still here.

"I don’t feel safe"

I chill with a small group of people from my wing, and when we were in the cell and heard what the Home Office said [about detainees being dangerous criminals]. We all just started debating. We couldn’t believe that the Home Office said that. One of my friends got a bit upset – he had a bit of a cry.

I’m not a murderer, I’m not a dangerous criminal. I was just someone who was doing as he was told, you get what I mean? Then for me to be labelled like that – I just felt disappointed.

If you ask me about my memories of Holland, they’re very vague because I left there when I was six. My life has been here. I feel 100 percent British – apparently, I sound British. I have no family in the Netherlands whatsoever.

They’re keeping me in this place, and they are saying that we’re not going to get coronavirus while we’re here. But you’ve got officers that are going outside and coming in and outside, and coming in, 24/7. And they’re not even wearing gloves, they’re not wearing masks. So I do get a bit paranoid.

I don’t feel safe. Just this morning, there was an officer who I haven’t seen in four or five weeks, and he looks very ill. That was enough to make me paranoid.

It’s not good to be left in the room alone with your thoughts, because you can lose your mind doing that. I’d prefer to be at home with my family doing isolation rather than being in here with people I don’t know.